6.2 The Kelly criterion#

The Kelly criterion determines the size of a bet in a repeated game with binary outcomes. The analysis was proposed in 1956 by John Kelly at Bell Laboratories. Kelly identified an analogy between gambling on binary outcomes and Claude Shannon’s work on encoding information for transmission on noisy channels. Kelly used the analogy to show

The maximum exponential rate of growth of the gambler’s capital is equal to the rate of transmission of information over the channel.

This idea actually predates Kelly. In 1738, Daniel Bernoulli offered a resolution to the St. Petersburg paradox proposed by his cousin, Nicholas Bernoulli. The resolution was to allocate bets among alternative outcomes to produce the highest geometric mean of returns. Kelly’s analysis has been popularized by William Poundstone in his book “Fortune’s Formula”, and picked up by gamblers with colorful adventures in Las Vegas by early adopters though the result laid in obscurity among investors until much later.

This notebook presents solutions to Kelly’s problem using exponential cones. A significant feature of this notebook is the inclusion of risk constraints recently proposed by Boyd and coworkers. These notes are based on recent papers by Busseti, Ryu, and Boyd (2016), Fu, Narasimhan, and Boyd (2017). Additional bibliographic notes are provided at the end of the notebook.

import sys, os

if 'google.colab' in sys.modules:

%pip install idaes-pse --pre >/dev/null 2>/dev/null

!idaes get-extensions --to ./bin

os.environ['PATH'] += ':bin'

solver = "ipopt"

else:

solver = "mosek_direct"

import pyomo.kernel as pmo

SOLVER = pmo.SolverFactory(solver)

assert SOLVER.available(), f"Solver {solver} is not available."

Optimal Log Growth#

The problem addressed by Kelly is to maximize the rate of growth of an investor’s wealth. At every stage \(n=1,\dots,N\), the gross return \(R_n\) on the investor’s wealth \(W_n\) is given by

After \(N\) stages, this gives

Kelly’s idea was to maximize the mean log return. Intuitively, this objective can be justified as we are simultaneously maximizing the geometric mean return

and the expected logarithmic utility of wealth

The logarithmic utility provides an element of risk aversion. If the returns \(R_i\)’s are independent and identically distributed random variables, then in the long run,

such that the optimal log growth return will almost surely result in higher wealth than any other policy.

Modeling a Game with Binary Outcomes#

The classical presentation of the Kelly Criterion is to consider repeated wagers on a gambling game with binary outcomes. For each stage, a wager of one unit returns \(1+b\) with probability \(p\) if successful, otherwise the wager returns nothing. The number \(b\) refers to the “odds” of game. The problem is to determine what fraction of the gambler’s wealth should be wagered on each instance of the game.

Let \(w\) be the fraction of wealth that is wagered on each instance. Depend on the two possible outcome, the gross return at any stage is

The objective is to the maximize the expected log return

The well-known analytical solution \(w^*\) to this problem can be calculated to be

We can use this analytical solution to validate the solution of this problem that we will now obtain using conic optimization.

Conic Optimization#

Recall that an exponential cone is a convex set \(\mathbf{K}_{\mathrm{exp}} \) of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) whose points \((r, x, y)\) satisfy the inequality

or the inequalities \(r \geq 0\) and \(y \leq 0\) if \(x=0\).

Introducing two auxiliary variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) and taking the exponential of the terms in the objective function, we obtain

and

With these constraints, Kelly’s problem becomes

The following code shows how to obtain the optimal solution using the conic optimization functions of the Pyomo kernel library and the Mosek solver.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# parameter values

b = 1.25

p = 0.51

# conic optimization solution to Kelly's problem

def kelly(p, b):

m = pmo.block()

# decision variables

m.q1 = pmo.variable()

m.q2 = pmo.variable()

m.w = pmo.variable(lb=0)

# objective

m.ElogR = pmo.objective(p * m.q1 + (1 - p) * m.q2, sense=pmo.maximize)

# conic constraints

m.t1 = pmo.conic.primal_exponential.as_domain(1 + b * m.w, 1, m.q1)

m.t2 = pmo.conic.primal_exponential.as_domain(1 - m.w, 1, m.q2)

return m

m = kelly(p, b)

SOLVER.solve(m)

print(f"Conic optimization solution for w: {m.w(): 0.4f}")

# analytical solution to Kelly's problem

w_analytical = p - (1 - p) / b if p * (b + 1) > 1 else 0

print(f"Analytical solution for w: {w_analytical: 0.4f}")

Conic optimization solution for w: 0.1180

Analytical solution for w: 0.1180

Risk-constrained version of the Kelly’s problem#

Following Busseti, Ryu, and Boyd (2016), we consider the risk-constrained version of the Kelly’s problem, in which we add the constraint

where \(\lambda \geq 0\) is a risk-aversion parameter. For the case with two outcomes \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) with known probabilities \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) considered here, this constraint rewrites as

When \(\lambda=0\) the constraint is always satisfied and no risk-aversion is in effect. Choosing \(\lambda > 0\) requires outcomes with low return to occur with low probability and this effect increases for larger values of \(\lambda\). A feasible solution can always be found by setting the bet size \(w=0\) to give \(R_1 = 1\) and \(R_2 = 0\).

This constraint can be reformulated using exponential cones. Rewriting each term as an exponential results gives

We previously introduced two auxiliary real variables \(q_1,q_2 \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(q_i \leq \log(R_i)\), using which we can reformulate the risk constraint as

Introducing two more non-negative auxiliary variables \(u_1,u_2 \geq 0\) such that \(u_i \geq e^{\log(p_i) - \lambda q_i}\), the risk constraint is given by

For fixed probabilities \(p_1=p\) and \(p_2=1-p\), odds \(b\), and risk-aversion parameter \(\lambda \geq 0\), the risk-constrained Kelly bet is a solution to the conic optimization problem rewrites as

The following cell solves this problem with a Pyomo model using the Mosek solver.

# parameter values

b = 1.25

p = 0.51

lambd = 3

def kelly_rc(p, b, lambd):

m = pmo.block()

# decision variables

m.q1 = pmo.variable()

m.q2 = pmo.variable()

m.w = pmo.variable(lb=0)

# objective

m.ElogR = pmo.objective(p * m.q1 + (1 - p) * m.q2, sense=pmo.maximize)

# conic constraints

m.t1 = pmo.conic.primal_exponential.as_domain(1 + b * m.w, 1, m.q1)

m.t2 = pmo.conic.primal_exponential.as_domain(1 - m.w, 1, m.q2)

# risk constraints

m.u1 = pmo.variable(lb=0)

m.u2 = pmo.variable(lb=0)

m.r0 = pmo.constraint(m.u1 + m.u2 <= 1)

m.r1 = pmo.conic.primal_exponential.as_domain(m.u1, 1, np.log(p) - lambd * m.q1)

m.r2 = pmo.conic.primal_exponential.as_domain(m.u2, 1, np.log(1 - p) - lambd * m.q2)

return m

# conic optimization solution to the risk-constrained version of Kelly's problem

m = kelly_rc(p, b, lambd)

SOLVER.solve(m)

print(f"Risk-constrainend solution for w: {m.w(): 0.4f}")

Risk-constrainend solution for w: 0.0589

Simulation#

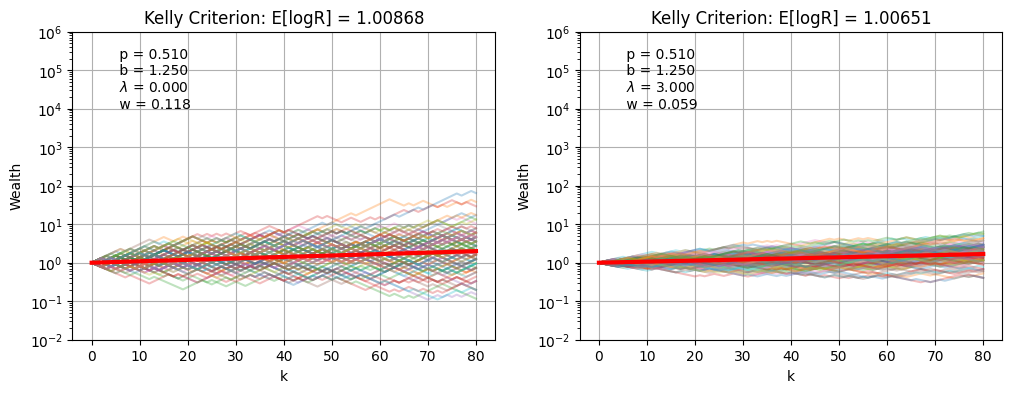

The following cells simulate the performance of the Kelly Criterion both with and without risk constraints. Compare the cases by comparing the log mean growth, which is reduced by presence of risk constraints, and the portfolio draw down for the most pathological cases, which is improved by the presence of risk constraints.

def kelly_sim(p, b, lambd=0, K=None, ax=None):

m = kelly_rc(p, b, lambd)

SOLVER.solve(m)

w = m.w()

m = p * np.log((1 + b * w)) + (1 - p) * np.log((1 - w))

if K is None:

K = int(np.log(10) / m)

if ax is None:

_, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

# monte carlo simulation and plotting

for n in range(0, 100):

W = [1]

R = [[1 - w, 1 + w * b][z] for z in np.random.binomial(1, p, size=K)]

R.insert(0, 1)

ax.semilogy(np.cumprod(R), alpha=0.3)

ax.semilogy(np.linspace(0, K), np.exp(m * np.linspace(0, K)), "r", lw=3)

ax.set_title(f"Kelly Criterion: E[logR] = {np.exp(m):0.5f}")

s = f" p = {p:0.3f} \n b = {b:0.3f} \n $\lambda$ = {lambd:0.3f} \n w = {w:0.3f}"

ax.text(0.1, 0.95, s, transform=ax.transAxes, va="top")

ax.set_xlabel("k")

ax.set_ylabel("Wealth")

ax.grid(True)

ax.set_ylim(0.01, 1e6)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

kelly_sim(p, b, lambd=0, K=80, ax=ax[0])

kelly_sim(p, b, lambd=3, K=80, ax=ax[1])

Bibliographic Notes#

The Kelly Criterion has been included in many tutorial introductions to finance and probability, and the subject of popular accounts.

Poundstone, W. (2010). Fortune’s formula: The untold story of the scientific betting system that beat the casinos and Wall Street. Hill and Wang. https://www.onlinecasinoground.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Fortunes-Formula-boek-van-William-Poundstone-oa-Kelly-Criterion.pdf

Thorp, E. O. (2017). A man for all markets: From Las Vegas to wall street, how i beat the dealer and the market. Random House.

Thorp, E. O. (2008). The Kelly criterion in blackjack sports betting, and the stock market. In Handbook of asset and liability management (pp. 385-428). North-Holland. https://www.palmislandtraders.com/econ136/thorpe_kelly_crit.pdf

The utility of conic optimization to solve problems involving log growth is more recent. Here are some representative papers.

Busseti, E., Ryu, E. K., & Boyd, S. (2016). Risk-constrained Kelly gambling. The Journal of Investing, 25(3), 118-134. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1603.06183.pdf

Fu, A., Narasimhan, B., & Boyd, S. (2017). CVXR: An R package for disciplined convex optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.07582. https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.07582